Cloverfields as of June 2018: Layers of Paint of the Highly-Original Cornice are Analyzed, and the House and Gardens are Documented for the Collections of the Library of Congress

/Paint Analysis of the Cornice

Dr. Susan L. Buck, PhD is a conservator specializing in the analysis and conservation of painted surfaces on wooden objects and architectural materials. She has analysed paint and finishes at Mount Vernon, Monticello, Montpelier, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the World Monuments Fund Qianlong Garden Conservation Project in The Forbidden City in Beijing. In the video above, she shows us how she analyzed a paint sample from the original cornice of the Cloverfields house.

Some background information on the cornice explains why analyzing it is so important. As an architect, I find it notable that the modillions (brackets) of the cornice are actually the ends of the floor joists. In contemporary buildings the modillions are applied to the outside of the building; they do not continue from the inside. In some classical temples modillions are made of stone — not wood, as in this case — and they are meant to represent the wood joist protruding over the beam. In the case of Cloverfields, there is an actual connection between the floor joists and the modillions. This makes the cornice of the Cloverfields house quite unique, and turns it into one of its more historically relevant architectural features.

Since it was first built during the eighteenth century, the cornice has been painted over several times. At the beginning of the twentieth century it was covered, so it was not visible until recently, when we discovered it and we took wood and paint samples from it.

The photo below shows the cornice before it was boxed. The photo was provided to us by the Pippin family, who lived in the house for decades during the twentieth century. We are very thankful for their contribution.

Photo graciously provided by the pippin family. You can see the original cornice of the house, from where a sample of paint was taken and analyzed.

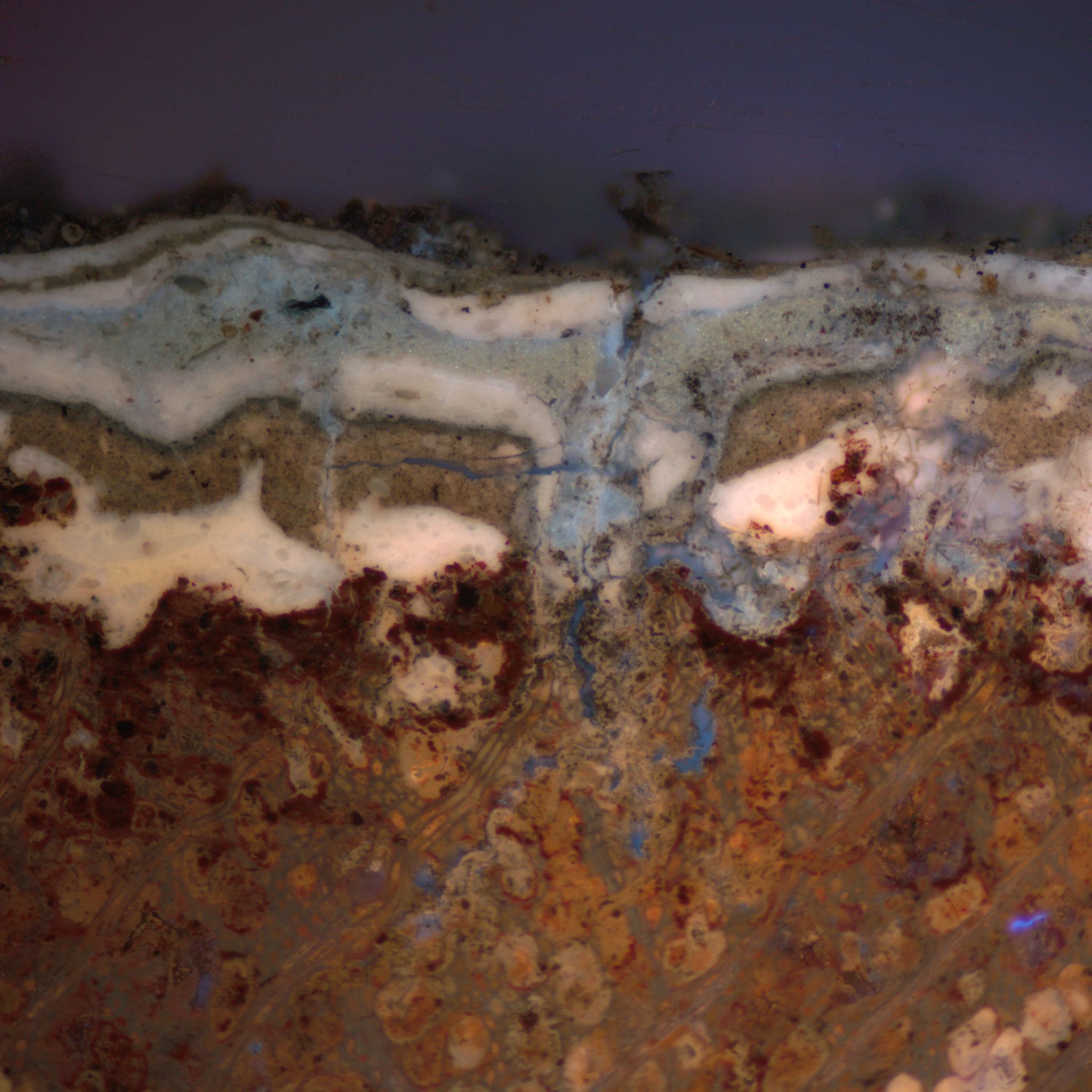

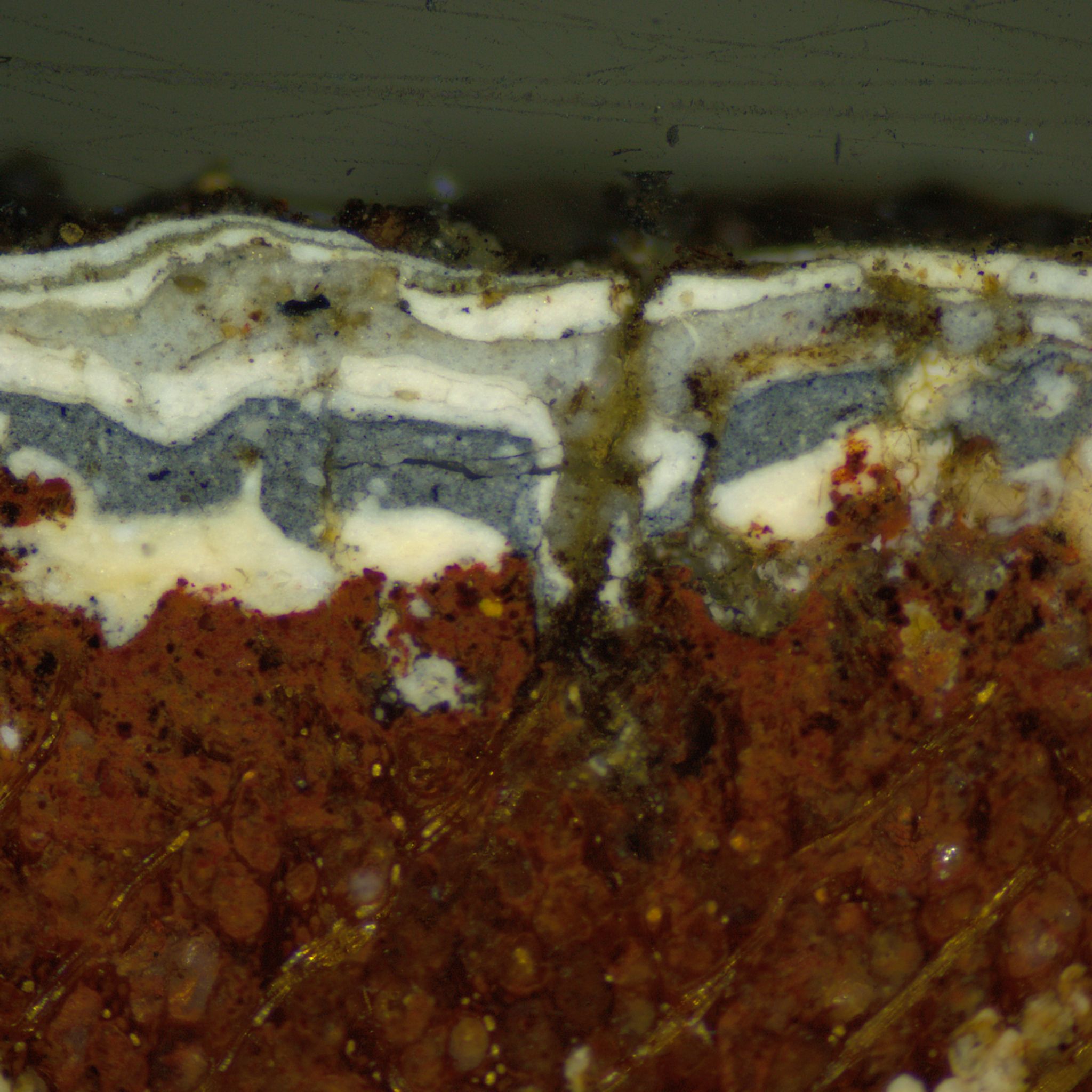

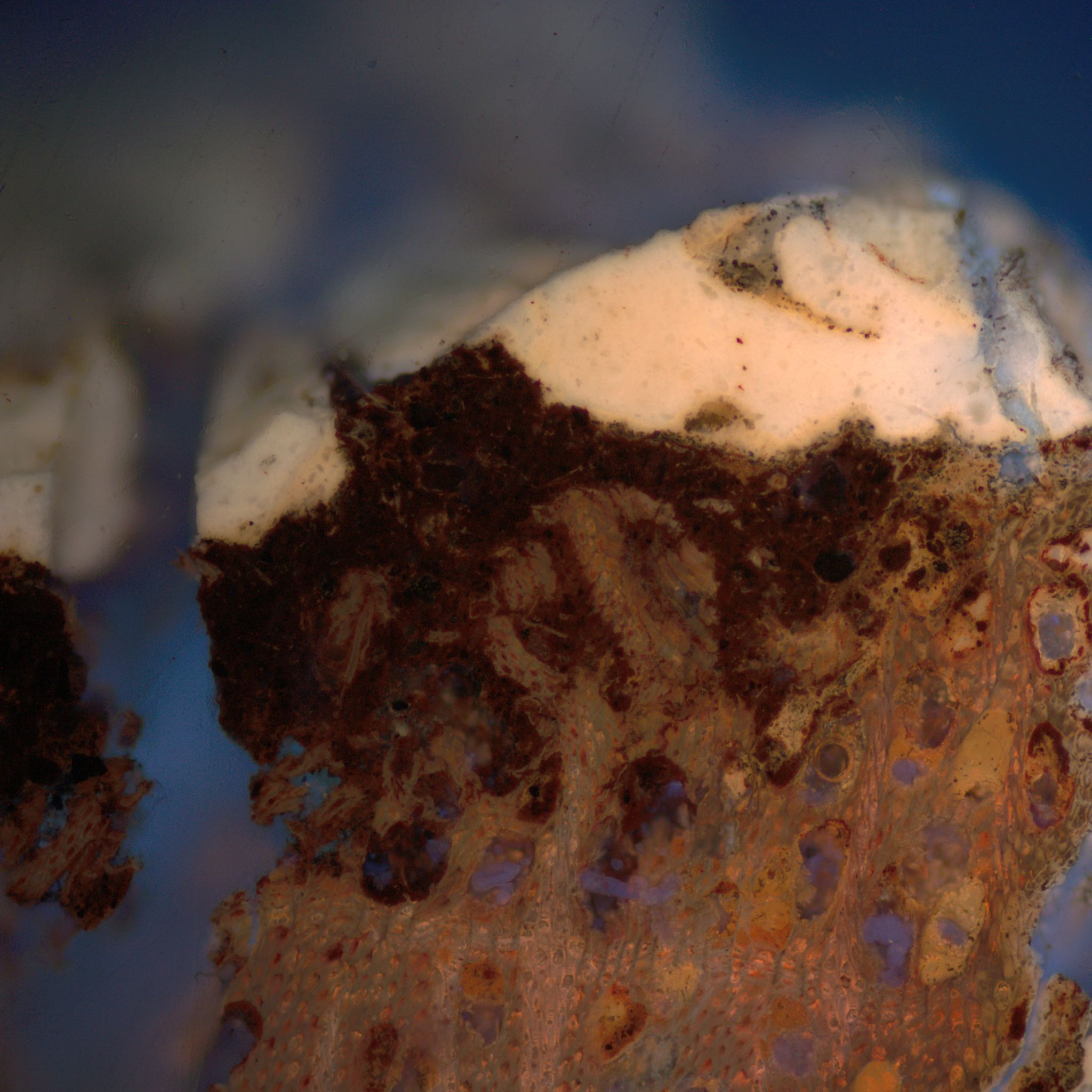

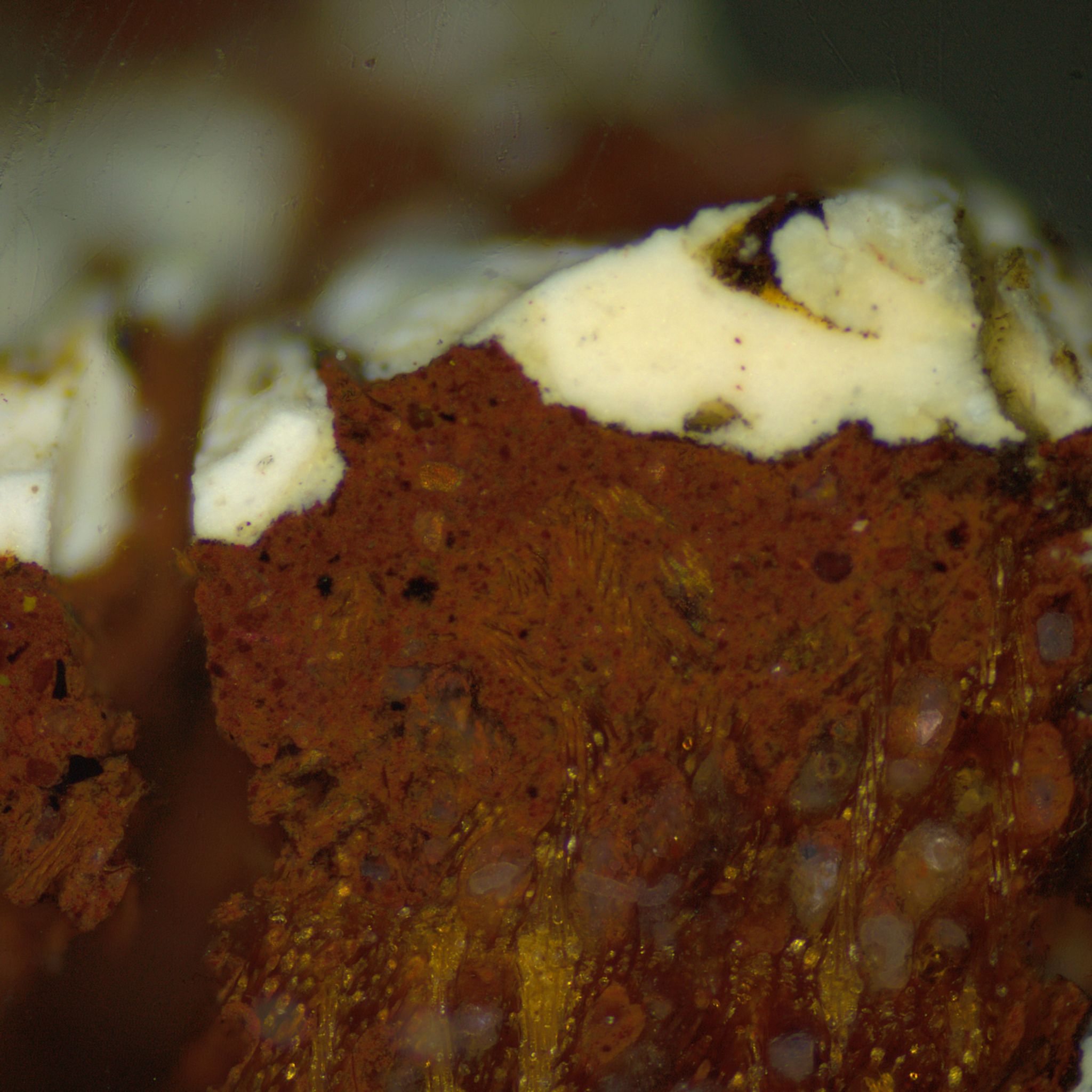

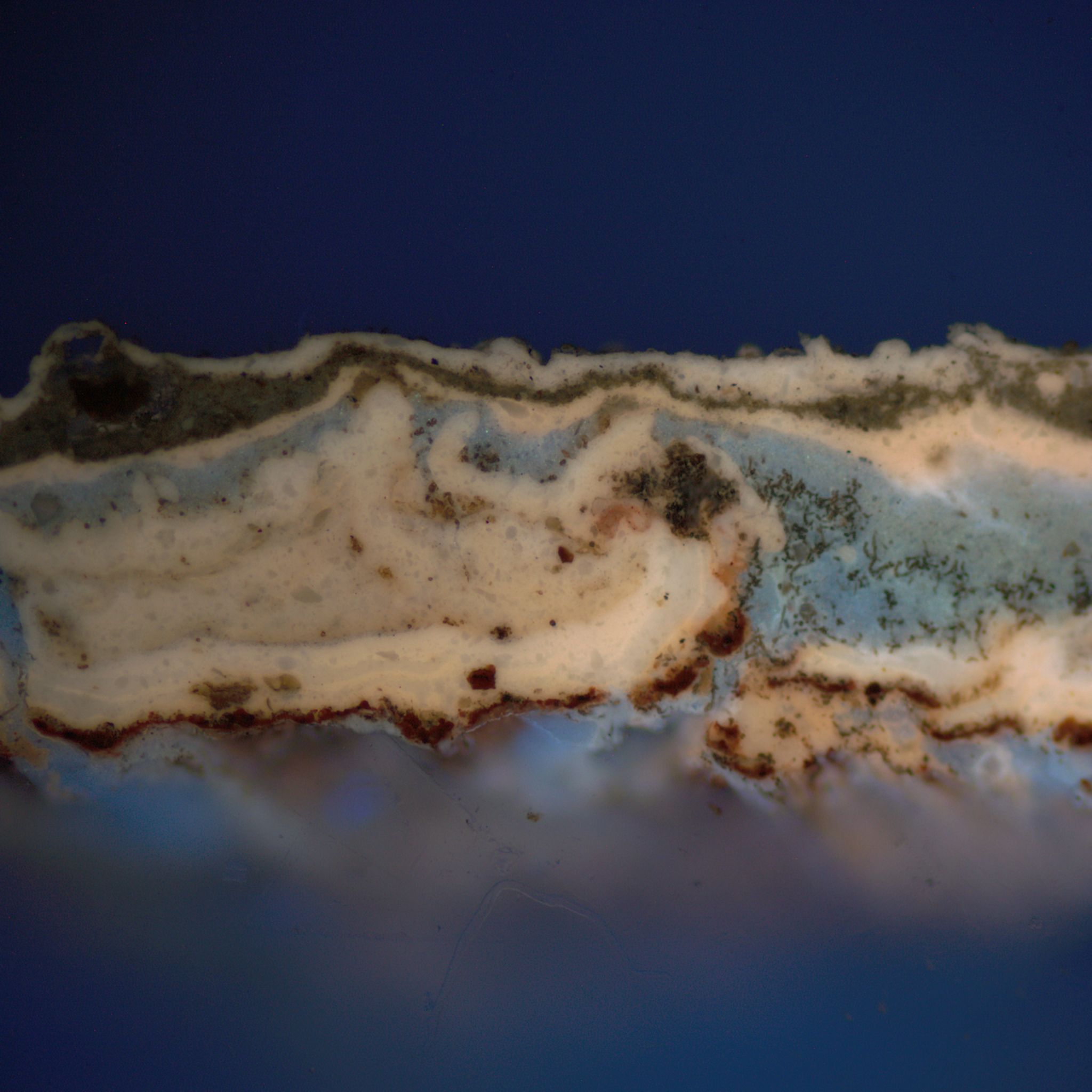

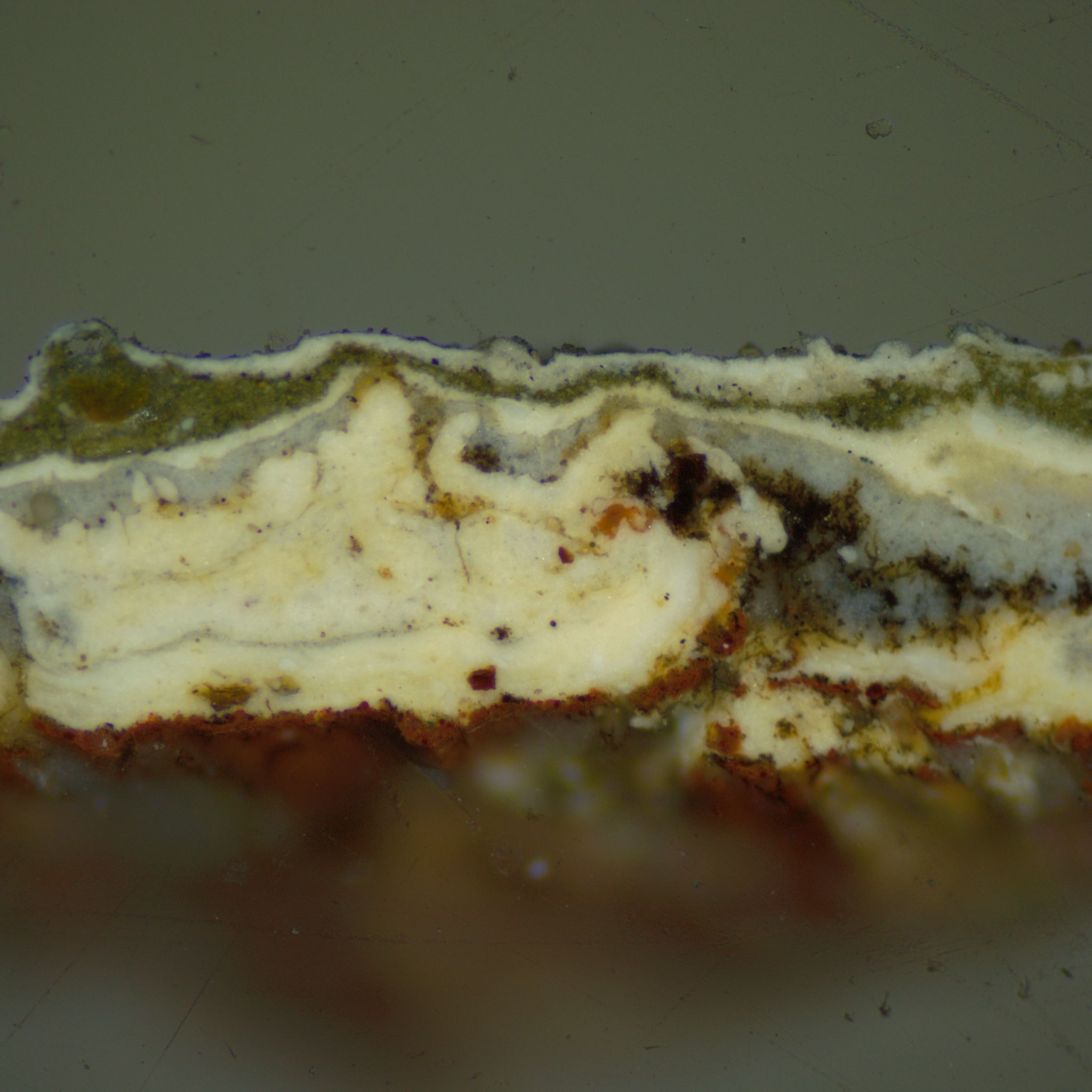

Dr. Buck took a sample of the original cornice to her lab, where she placed it under a microscope. Thanks to a specialized software, the microscope sent images to a computer screen. This allowed her to take "pictures" of the sample and to explore original colors, surviving colors, sheen, lead content, finish type, pigments, media employed, application techniques, and weathering characteristics.

In the video Dr. Buck expounds on the weathering characteristics of the layers of paint applied to the cornice. She placed a tiny sample of the layers under the microscope to look for cracks, dirt and other proof of exposure to outside elements. This exposure means that that specific layer of paint was actually used and could be seen from the outside. She was able to find plenty of evidence of exposure to rain and sun in the wooden sample—which, she clarifies, is good.

The cornice sample is only one of the over 90 samples taken. After coordinating with one of the historians of the team, Willie Graham, Dr. Buck and her team went through the house and inspected different areas under light and magnification to help them decide the specific places from where to take the samples. They looked for those areas that seemed to have had paint accumulation. Ideal samples will have multiple layers of paint to help put together a chronology.

Once the samples are taken, they are once again inspected under low magnification to sort through and find which have the best, and potentially most informative, paint chronology. Dr. Buck explains: "I am looking for paint samples that have a little bit of wood attached to the paint layers and seem to be representative of the best sequences of layers." These samples are then cast into small polyester and resin cubes that can be ground and polished for examination under the microscope.

The microscope examination is the most revealing part of the paint analysis process. "It's those cross sections under the microscope that give you this really powerful tool to figure out changes over time and comparisons between original surfaces and later surfaces," Dr. Buck points out. The different light filters of the microscope allows Dr. Buck to see cross sections of the samples under different levels of the UV spectrum. Photos below show various samples being compared with different filters.

Dr. Buck also explains that although color determination is an important goal of the analysis, this is not its exclusive purpose. Another purpose of the paint analysis is to show how different architectural spaces relate to each other. In Dr. Buck's own words: "It is far more than figuring out what color it was. It is really understanding how elements within a room relate, or how elements in one room relate to an adjacent room, how architectural fragments might be put back into context based on the paint chronologies." Paint analysis therefore provides physical evidence to corroborate —or disproof— the theories of the historians, archaeologists and architects on how, when, and what materials were used when the paint was applied.

Photographs and Drawings Document the Cloverfields House and Gardens for Future Generations

In the meantime, I have been working closely with my architectural team and with David Berg to document the house and grounds as they stand today. My team created detailed drawings, and Berg took photographs. The drawings and the photographs will be added to two different collections of the Library of Congress: the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) and the Historic American Landscapes Survey (HALS).

The photos below show our architectural team conducting field measurements and documenting architectural features per HABS requirements. Thomas H. Haley can be seen over the drawing board, and Jeffrey Renshaw can be seen conducting measurements. The tool you can see in Renshaw's hands is a contour gauge, which is especially helpful to accurately document molding profiles. Many long days were filled with meticulous measurements of the thickness of each wall and the dimensions of each room.

Photographs of the house taken during the 1960s are already part of the HABS. The gardens, however, were not documented. I thought it was important to update the HABS records on the house, and to introduce the Cloverfields landscape in the HALS collection. The team then contacted Berg, whose experience and specialized equipment allows him to take photographs in the format required by the Library of Congress.

The required format, Berg clarifies in the video, is "large format, black and white, and archivally processed, which means that there's no trace of chemicals in it when we are done." To meet these requirements Berg utilizes the large format film camera you can see in the video and in the photos below. This type of camera, Berg tells us, can produce a "highly detailed negative, which cannot be equaled to a digital one." The library asks for these specific negatives because it predicts they will last for a long time—at least 500 years.

Below you can see Berg with his camera and some of the over 60 photos of the house and grounds that he took. Their tonal contrast presents a dramatic and accurate representation of the house and gardens as they sit today.

In a few months, the photographs and the drawings will become part of the collections of the Library of Congress, and will be accessible to future generations of investigators.

By: Devin Kimmel, AIA, ASLA, for the Cloverfields Preservation Foundation

Photography by Pete Albert, Willie Graham, and Devin Kimmel

Video by StratDV Video Production