Negotiating Friendship, Courtship, and Love in the Eighteenth Century

/In honor of Valentine’s Day, this month’s newsletter features stories of love, marriage, and a few less clear-cut relationships. Also in this issue is new research on artist John Hesselius (1728-1778), his work, and his connection with Cloverfields.

Canvas Connections: Exploring the World of the Artist John Hesselius (1728-1778) and his Family at Cloverfields

by Rachel Lovett, Furniture Consultant

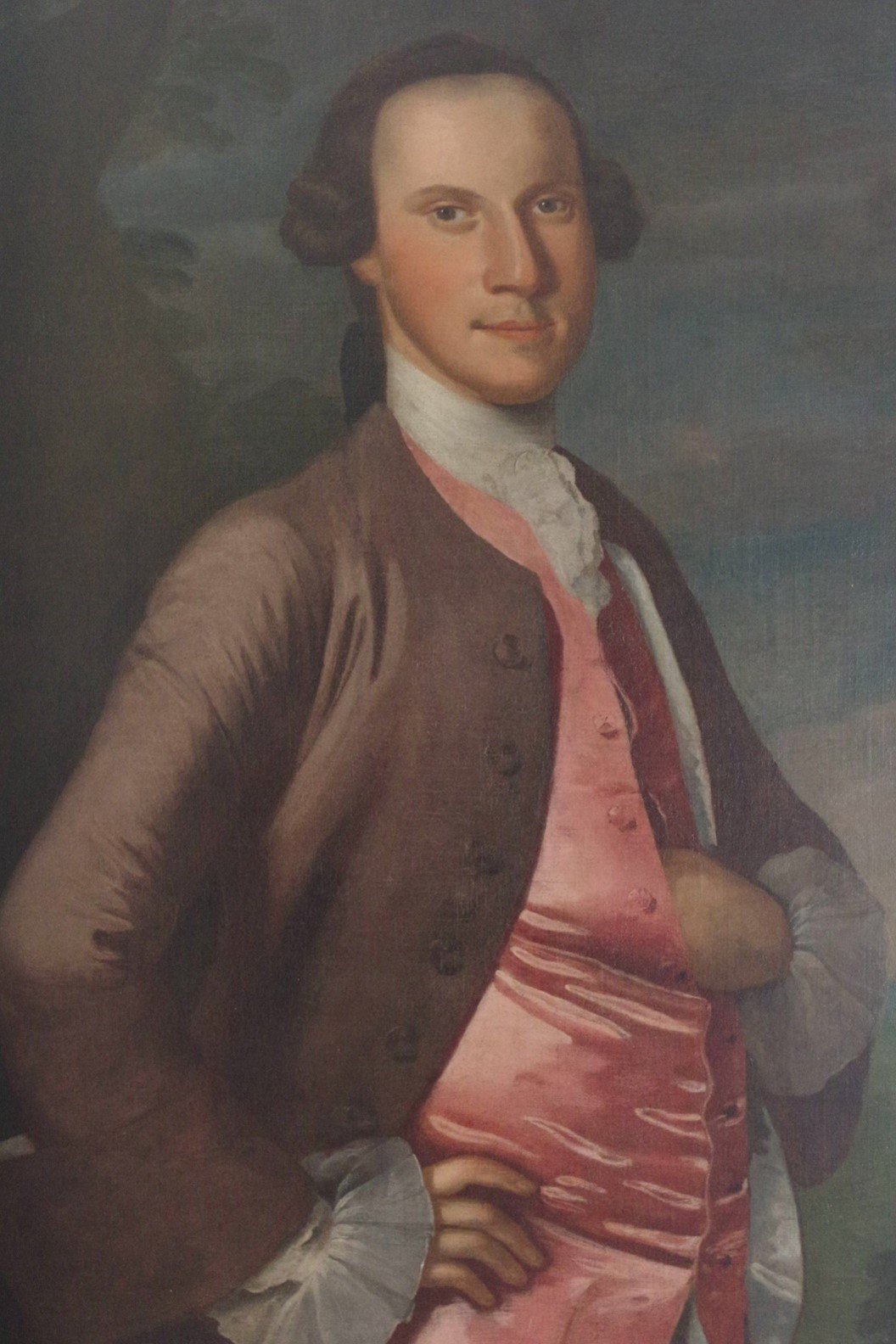

Restored to the year 1784, Cloverfields depicts the home of Colonel William Hemsley (1727-1812). One of the most authentic items acquired to date is the portrait of Hemsley (Image 1) which hangs in the parlor. In the portrait, Hemsley appears to be in his early thirties, posed against a dark background, depicting a forest landscape with a tree on the left.

He wears a light brown jacket with his left hand in his pink silk waistcoat, with a white cravat and undershirt. Pink was regarded as a fashionable masculine color in the period, often associated with hunting. One hand in the waistcoat was a typical gentleman’s pose in the period, seen on numerous contemporary portraits. His brown wig, common in the mid-18th century, is slightly receded and reveals a shaved head and natural brown hair, while his gaze is directly facing the viewer.

Oil on canvas, this piece was painted by the artist John Hesselius (1728-1778). Hesselius also painted Hemsley’s mother Anna Maria, step-father Robert Lloyd, and two younger half-sisters, Anna Maria and Deborah, likely contemporaneously to this portrait.[1]

Done from life, likely at Cloverfields, Hesselius completed the family before 1763, as Hemsley’s mother, Anna Maria Tilghman Hemsley Lloyd (1709-1763), died that year. Sometime later, Hesselius made a miniature copy of Hemsley’s mother’s portrait, and it was given to Hemsley during his lifetime. A small note inscribed on the back reads "$7.00 / Loaned to Wm Hemsley / during his life - at his death / to be returned to A.M. Tilghman / or Augustina Forman".[2]

This likeness of his mother was a treasured keepsake for Hemsley kept in his personal possessions.

image 1: WILLIAM HEMSLEY (1736-1812), AS PAINTED BY JOHN HESSELIUS, IN THE 1760S. COURTESY OF THE CLOVERFIELDS PRESERVATION FOUNDATION.

Beyond the Hemsley family, Hesselius’ client list literally painted a picture of the landed gentry in Virginia and Maryland. Traditionally, artists in early America were seen as mechanical craftsmen, not any different than a blacksmith or a tailor. However, Hesselius was unique, as he not only painted the landed gentry but also rose to become one of them.

Hesselius was born in 1728 and emerged as a prominent portraitist in the mid-Atlantic region, particularly in Maryland, during his most prolific period spanning roughly from 1750 to 1763. His artistic lineage traces back to Gustavus Hesselius (1682-1755), his father and a Swedish-born painter, who is recognized as one of the earliest trained artists to practice in America.

Hesselius embarked on his career as a portrait artist around 1750, evident from the dated works attributed to him. It's speculated that he might have worked alongside fellow artist Robert Feke (1707-1752) that year.

Hesselius’s style follows English Baroque and Rococo traditions. His portraits often exhibit generic and repetitive facial features. His early attempts at capturing human anatomy, particularly in the depiction of hands and facial features, display a certain degree of challenge. Hesselius's artistic evolution can be traced to the works of Robert Feke, leaving an impression on his own artistic expression. In contrast to the restrained style of his father, Gustavus Hesselius, John found inspiration in Feke's vibrant and decorative approach.

Feke's style permeates Hesselius's canvases, especially in the use of vibrant colors to depict textiles. Moreover, Hesselius's artistic journey was also shaped by John Wollaston (active between 1742 and 1775), a British artist who later moved to the colonies and did a large volume of work in Maryland from 1753 to 1754.

In contrast to other prominent portraitists of the time, such as John Singleton Copley, who sought the more developed centers of painting in London, Hesselius remained rooted in the American Colonies. His steadfast commitment to the late English Baroque and English Rococo traditions, coupled with a propensity for integrating external influences, positions John Hesselius as a distinctive figure in the unfolding narrative of colonial American portraiture.

While residing in Philadelphia for several years, Hesselius frequently journeyed through Virginia and Maryland, seeking commissions for his portraiture. By approximately 1759, he settled in Anne Arundel County, Maryland. In the early 1760s he trained future artist Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) of Annapolis, who traded three saddles to have Hesselius teach him to paint. Peale would later rise to be known as the portrait painter of the American Revolution and one of the most celebrated influential trendsetters in early America.

In July of 1763, at age 35, Hesselius married Mary Woodward, a prosperous widow with four young children who owned Primrose Hill (Image 2), a 500-acre estate in Annapolis south of the capitol. This marriage provided entrée into a status seldom seen for a portrait painter in the period.

Image 2: Primrose hill, built circa 1765, owned by JOHN HESSELIUS AND HIS WIFE Mary woodward hesselius. The building is still extant and privately owned.

The couple suffered the loss of three children who died young before having three healthy daughters: Charlotte, born in 1770; Caroline, born in 1773; Elizabeth, born in 1775; and one son, John, born in 1777.

Despite maintaining his artistic endeavors in Maryland and Virginia, Hesselius found himself occupied with managing two estates, Primrose Hill and Bellefield, located north of Annapolis on the Severn River. He also dedicated significant time to religious activities as a churchwarden in Annapolis at St. Anne’s Episcopal Church.

Sadly, for Hesselius’ young family and his patrons, he passed away in 1778 at the age of 50. His estate's inventory suggests a man of considerable wealth, possessing a multitude of skills beyond his artistic talents. He owned numerous scientific instruments, including a camera obscura, a microscope, three violins, a harpsichord, and a guitar, all relatively rare for 18th-century America.

The relationship between Hemsley and Hesselius continued through the next generation with their children. A July 14th, 1793 letter, now owned by CPF, references social gatherings between Hemsley’s second-eldest daughter Charlotte, and Hesselius’ second daughter Caroline, mentioned only as Miss Hesselius.[3]

In the letter addressed to Edward Lloyd IV, Col. William Hemsley follows up on an invitation for the Lloyds to visit the next day. The invitation also included the couple’s daughter Rebecca and houseguests, Miss Anderson and Miss Hesselius, who were to remain overnight as guests of Charlotte.

As detailed in the accompanying article, concern that Rebecca Lloyd might encounter a romantic interest frowned upon by her parents during her visit to Cloverfields had put the visit into question.

We do not know if Caroline Hesselius visited Cloverfields the next day. If so, she must have felt a twinge of joy and pain seeing her late father’s work on display.

One can imagine her lingering in the parlor, contemplating her father’s familiar style and thinking of him painting at Cloverfields three decades earlier.

Although no image exists of Caroline Hesselius, there is an image of her older sister Charlotte (Image 3). Charlotte, the eldest surviving Hesselius daughter, was married to Thomas Jennings Johnson, son of Maryland’s first governor at the time of the letter.

image 3: cHARLOTTE HESSELIUS (1770-1794) ELDEST SURVIVING CHILD OF ARTIST JOHN HESSELIUS. from “Certain Worthies and Dames of Old Maryland,” In THe Century Illustrated Magazine, February 1896, Vol. Li.

Charlotte Hesselius was known as a notorious flirt in her day. Her mother Mary wrote a poem about her. A verse from it says, “Too thoughtless for conquest, too careless to please. No ambition she knows but to live life at ease.”[4] Sadly, Charlotte died in childbirth in 1794, just two years into her marriage.

Since the moment Hesselius carefully laid down his brush to complete the canvas of Col. William Hemsley, the portrait has borne witness to the unfolding chapters of American history. Through periods of societal change, cultural shifts, and historical milestones, the portrait remains a steadfast link to the past. It has witnessed the comings and goings of different owners, each inheriting not just an artwork but a piece of the rich tapestry of Hemsley's legacy. In the gaze of Hemsley, frozen in time by Hesselius's skillful hand, the portrait invites reflection on the interplay between art and the ever-evolving human experience.

[1] All remain in private collections as of February 2024.

[2] Information according to the Frick Art Reference Library. https://library.frick.org/permalink/01NYA_INST/1qqhid8/alma991013416049707141. The piece was later returned to the family of Hemsley’s half sister Deborah and it is still in a family private collection.

[3] Caroline’s elder sister Charlotte and younger sister Elizabeth were already married by 1793, leaving her as the only possibility to be Miss Hesselius. The elder Charlotte married Thomas Johnson (son of Maryland’s First Governor), and the younger Elizabeth married Walter Dulany on June 5th, 1792, in what appears to be a double ceremony. Caroline would later go on to marry Judson Claggett in March of 1795.

[4] The full contents of the poem can be found in The Century Magazine Volume LI No. 4, dated February 1896, in an article entitled Certain Worthies and Dames of Old Maryland on pages 490-491.

Unsuitable Suitors and Protective Patriarchs

The Story of Rebecca Lloyd and Joseph Hopper Nicholson

On July 14, 1793, Col. Hemsley and his second wife Sally found themselves in an awkward position. They had invited Col. Edward Lloyd IV, his wife Elizabeth, their daughter, referred to in letters as Miss Lloyd, and house guests, Miss Henderson and Miss Hesselius, to dine the next day. The Hemsley's thirty-three-year-old daughter Charlotte had extended the invitation to have the young women spend the night at Cloverfields as her guests.

We know this from a letter Hemsley wrote to Lloyd in which the former entreats the latter not to cancel the date out of fear of an unwelcome encounter. [1]

Miss Henderson's identity remains unknown. Miss Hesselius, we learned from Rachel Lovett's accompanying article, is Caroline, the second of three daughters of portrait painter John Hesselius and his wife Mary Young Woodward. Miss Lloyd is obviously Rebecca Lloyd (1771-1848), the second daughter of Col. Edward Lloyd IV (1744-1796) of Wye House and the former Elizabeth Tayloe (1750-1725) of Mount Airy in Virginia.

Edward Lloyd headed one of the Eastern Shore's wealthiest and most influential families and, in 1767, made a brilliant marriage to Elizabeth, daughter of Col. John Tayloe II (1721-1779). With over 40,000 acres under his control, Tayloe was one of Virginia's largest landowners and at the top of Virginia politics and society. Tayloe’s wealth and holdings exceeded Lloyd’s, but the match was mutually beneficial and brought each business and political connections in the neighboring colony.

The Lloyds were naturally protective of Rebecca and likely hoped she would make an equally suitable marriage, which brings us back to Hemsley's awkward position. Rebecca was receiving romantic overtures from an ambitious local lawyer named Joseph Hopper Nicholson (1771-1817). While Rebecca apparently welcomed Nicholson's attention, her parents did not.

Image 1:: Edward Lloyd, IV, wife Elizabeth Tayloe Lloyd and daughter Ann, ca. 1771 by Charles Willson Peale. Image courtsey of Winterthur Museum.

Previously, Col. Hemsley assured Mrs. Lloyd that Rebecca would not encounter the young man while at Cloverfields, but the day before the event, Hemsley found himself needing to reaffirm his promise. He wrote to Mr. Lloyd informing him Nicholson, in the company of two other young gentlemen, had unexpectedly visited the family a few nights before.

Fearing the Lloyds would hear, or perhaps had heard, of the visit and possibly think them complicit in the romance, Hemsley explained the circumstance. Sounding uncharacteristically embarrassed and apologetic, Hemsley told Lloyd that the visit was both extraordinary and unexpected, that he had no business with the man that would precipitate a call, and entreated them not to let the unanticipated event cause them to reconsider their visit.

Regrettably, we do not know if the Lloyds and young ladies visited Cloverfields as planned and can only speculate as to why the possibility of an encounter with Joseph Hopper Nicolson would scuttle the event.

Nicholson came from a well-regarded Chestertown family and inherited most of his father's modest but respectable estate. Nothing about his background appears objectionable, but perhaps the Lloyds thought a woman of Rebecca's position and status could do better than this young country lawyer.

The Hemsleys and Joseph's widowed mother, Mary, were then involved in an acrimonious land dispute. A month after the planned get-together, Hemsley wrote to Lloyd about the lawsuit and "Mary Nicholson's pretensions" to his land. Perhaps the Lloyd's disapproval stemmed from a similar interfamily dispute and not a personal objection to the young man.

Whatever the reason, in this case, the couple's desires won out over family misgivings. Rebecca and Joseph married three months later.

[1] Col. William Hemsley to Edward Lloyd IV. July 14, 1793. Cloverfields Preservation Foundation Collection.

A snowy winter Morning At Cloverfields, 2024. PHoto BY Sherri Marsh JOhns

A similiar Day a Century or more ago. Photo courtesey of Mary Callahan Piipin.

CPF congratulates Kimmel Studio Architects and Lynbrook of Annapolis for winning the 2023 American Institute of Architects, Chesapeake Bay Chapter, Honor and Preservation Award for Residential Renovation and Addition for their work at Cloverfields.

Architect Anees Ubaid (Kimmel Studio Architects) and Meredith Hillyer (President, Lynbrook of Annapolis) Display the award received at the November Ceremony. They are joined by project members Emely Trejo (left) and Lauren Schnable (right), both with Lynbrook of Annapolis.

An Offer of Marriage

Being lately so long in company with your sister, I feel such an attachment for her as induced me to make her a proposal to become one of my family

-Col. William Hemsley to William Tilghman, October 30th 1797

Valentine’s Day, of course, is the February holiday dedicated to celebrating romantic love. With antecedents in a pagan Roman fertility festival and the veneration of a 3rd-century martyred priest, the spirit of the holiday has strayed far from its origins.

We do not know if the Hemsleys celebrated Valentine’s Day, but they certainly would have been aware of it. By the 1750s, British friends and lovers of all classes exchanged tokens of affection or handwritten notes. The sentimental holiday did have its critics. On several occasions, “Mr. Town,” a commentator with the weekly London publication The Connoisseur took aim at its observers. In a 1754 essay, he mocked superstitious young women who used the occasion to employ “amorous sorcery.” For admirers squeamish about employing magic, there was poetry or love letters, and if they lacked the talent to pen their own sentiments, professional Valentine writers were there to help.

This increasing focus on what we now call romantic love created difficulties for controlling parents who expected their children to marry partners to secure alliances and consolidate wealth. One hundred years of marriages to first cousins suggests the Hemsleys, at least sometimes, married for such practical considerations. Decades of family correspondence routinely mentions upcoming marriages, but only Col. Hemsley’s 1797 letter confessing “an attachment” points to a union based on affection.[1]

Col. Hemsley intended first cousin Anna Maria “Nancy” Tilghman (1750- 1817) as his third wife. At age sixty-one, twice widowed, and with fortune and legacy established, he could afford to follow his heart, as indicated when he writes to Nancy’s brother, “As to pecuniary matters, I shall be entirely disinterested...” Hemsley asked Tilghman to put in a good word for him with his sister, which he apparently did, as Hemsley later thanked Tilghman for his “approbation.”

William Hemsley wrote of his feelings, but what were those of the intended bride? Unmarried at age forty-seven, did Nancy welcome the union and an opportunity to manage her own household? Or was she content, but since the death of her father three years earlier, feel a burden to her siblings and obligated to marry?

Whether out of affection or duty, only two months after receiving Hemsley’s proposal, the pair wed on December 26, 1797. Col. Hemsley tells Tilghman of the event and “hope neither of us will ever have cause to repent the connection” (Image 1).[2]

Image 1: Col. Hemsley writes to his cousin and brother-in-law william tilghman announcing his and nancy’s marriage.

On whether theirs was a happy union or a proverbial case of “Marry in haste, repent at leisure,” the record is silent. The marriage lasted for nearly fifteen years, concluding with Hemsley’s death in 1812.

[1] Col. William Hemsley to Hon. William Tilghman. October 30, 1797. William Tilghman Correspondence, Manuscript Collection #659, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

[2] Hemsley to Tilghman, January 7, 1797.

Unsuitable Suitors and Protective Patriarchs (continued)

Image 2: Joseph Hopper Nicholson (1770-1817) in an 1806 Miniature by Charles Balthazar Julien Fevret de Saint-Memin. Image Courtesey Maryland Center for History and Culture.

Image 3 : Rebecca Lloyd Nicholson (1771-1847). from “Certain Worthies and Dames of Old Maryland,” In THe Century Illustrated Magazine, February 1896, Vol. Li.

The Story of Mary “Polly” Tilghman and William Paca

On Valentine’s Day, 1782, marriage occupied the thoughts of Col. Edward Tilghman Sr. (1713-1785), but it was not the thrice-married octogenarian and uncle of Col. Hemsley who planned to wed.

An alarming rumor had reached Tilghman that his nineteen-year-old daughter Mary (1762-1793), known as Polly, would soon be engaged to a widower twice her age. The prospective groom was William Paca (1740-1799), a wealthy lawyer and politician best known today as one of Maryland’s four signers of the Declaration of Independence and builder of the William Paca House in Annapolis.

Except for age, Paca’s prominent position and large estate should have caused Tilghman to look favorably upon a match, but this was not the case. Accompanying news of the romance were stories questioning the gentleman’s character. Tilghman determined to find out if reports of the engagement were accurate. Instead of simply asking Polly, he sent a series of letters to male relatives asking what they had heard of the matter and their opinion of Paca. Tilghman’s concern, we learn, was not a matter of age but, as noted Annapolis historian Jean Russo put it, a question of reputation. [1]

Image 4: Edward Tilghman, Sr. (1713-1785), Uncle of Col. William Hemsley, by Charles Willson Peale. Source Find a Grave.com.

Tilghman’s first letter went to his son Edward Jr., known as Neddy, demanding “a very explicit detail of [his] knowledge of Mr. P’s character & circumstances & what you have heard & from whom, any way relative to them.” The son’s reply only heightened the father’s anxiety. Paca “in a very considerable degree wants integrity and veracity,” wrote Neddy, and close friends considered him “a man of deep malice and resentment.” Furthermore, he was a known womanizer, “[addressing] every woman as if he intended to make love to her…” To all this, he added, Paca was too old to marry his sister.

While the elder Tilghman expressed considerable concern about the former issues, about the latter, he responded in a shockingly callous manner for a father, telling Neddy, “my real opinion is he would outlast her… He is uncommonly robust and healthy. She [is] constitutionally delicate & tender & being from parents, both rather declining, cannot last long.”

Image 5: William Paca as painted by Charles Willson Peale in 1777, ten years before the described events took place. Image Courtesy Maryland State Archives. The original hangs in the Maryland State House in Annapolis.

A few days later, Tilghman wrote to his nephew, Col. William Hemsley, putting to him the same questions he asked of Neddy. The request left Hemsley in a delicate position. With family honor at stake, Uncle Ned required an honest answer, but he and Paca shared many connections. The pair had worked closely together during the Revolution, he was now a neighbor, and they saw each other socially.

In his carefully worded response, Hemsley denied knowing anything adverse about Paca’s character (other than recalling the ungracious and hasty manner in which Paca broke off his engagement to his cousin Nancy Tilghman). He admitted to hearing rumors of a possible engagement but denied first-hand knowledge of the matter. Mrs. Hemsley, he said, observed Paca shifting partners to dance with Polly, and she took Polly’s reaction when they danced or spoke to mean there was something to the report—or possibly the opposite, that Polly knew of the rumors and Paca’s attention embarrassed her.

Tilghman requested Hemsley cease discussing the matter with his wife: “I repeat my injunction of secrecy even from the wife of your bosom...” Why make such a request? On this question, Tilghman is straightforward, writing, “from constitution, education & habit, [women] are in my opinion unfit repositories for important secrets.” Ironically, he did not consider himself an “unfit repository” for having shared this important secret with numerous male relations or a hypocrite for asking them for what was essentially gossip about Paca.

Ten days after his initial inquiry and still not knowing his daughter’s relationship status, Edward Tilghman Sr. took up the question with one of the two persons with firsthand knowledge of the matter. Again, not his daughter, but Paca, to whom he wrote, inviting him not to his home but to meet discreetly at a clearing at the end of a cart road.

At the interview, Paca confessed he had hoped to make “an agreeable matrimonial connection,” and for some time, Polly had been “foremost in his esteem.” On more than that Paca equivocated. When Tilghman pressed him with Polly’s claim—apparently, father and daughter had finally got around to talking– that on the evening of a visit to the Coursey’s, Paca asked Polly “if she could love him,” and when she evaded, he “insisted she should consider if she could, which she promised him she would do.” Paca claimed no recollection of the exchange, but being drunk that night, or in his words, “a good deal enlivened by liquor,” he conceded the claim might well be true.

A month after voicing his concern to Neddy, Edward Sr. had somewhat softened his opposition to the match, but Neddy remained so steadfastly and vocally opposed that he feared Paca would challenge Neddy to a duel.

None of these letters take into consideration Polly’s opinion or make mention if it were known. Whether or not she married Paca seems to have been a matter for the men to work out among themselves. The story concludes without a wedding. Did Paca lose interest in Polly or cease his advances because of the family animus? Maybe Polly was the agent of her story after all, and after the promised consideration, she told Paca she could not love him. The following year, she married her first cousin, Richard Tilghman (1747-1805).

William Paca did not remarry. Sadly, Edward Tilghman’s prediction proved correct; Paca outlived Polly by six years.

[1] This story comes to us from A Question of Reputation: William Paca’s Courtship of Polly Tilghman (Annapolis: MD: Historic Annapolis, Foundation, 2000) by Jean B. Russo. The informative and entertaining book is out of print, but “Polly Tilghman’s Plight: A True Tale of Romance and Reputation in the 18th Century,” the 1997 Maryland Historical Society Magazine article which preceded the book, is available online at https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc5800/sc5881/000001/000000/000369/pdf/msa_sc_5881_1_369.pdf. The quoted letters are from Tilghman Papers at the Maryland Center for History and Culture.