Rest Assured: Bedchambers at Cloverfields Reimagined. Also, it is Harvest Time. Examining Changing Agricultural Practices, 1705-2025.

/fields of Corn and Soybeans flank most of the mile-long approach to Cloverfields. Native Americans cultivated corn and introduced the staple to European Settlers. In Contrast, farmers did not plant soybeans in signifcant quantities until after World War II. Photo By Sherri Marsh Johns.

Rest Assured: Bedchambers at Cloverfields Reimagined

by Rachel Lovett, Furnishings Consultant

Working on the restoration of Cloverfields is a rare opportunity to bring design, decorative arts, and social history together in one project. Recreating the 1784 home of Colonel William Hemsley and his family serves as both a historic canvas and a living laboratory, where period interiors are carefully researched, recreated, and reimagined to reflect the lives of its 18th-century occupants.

The installation of two historically informed bedsteads at Cloverfields in July 2025 marks a significant step forward in recreating the 1784 interiors. To bring this project to fruition, I worked closely with the talented Natalie Larson, the textile historian, who is well known in the field for producing the most authentic historic bed reproductions in the country.

In the 18th century, bedchambers were not only private spaces but also dynamic centers of domestic and social life. Far from serving solely as sleeping quarters, these rooms were stages where daily routines unfolded, from correspondence and household management to the intimate rhythms of family life, including childbirth, illness, and death. To furnish these rooms with accuracy is to restore the textures of lived experience and to better understand the values of comfort, status, and hospitality in late colonial Maryland.

The first phase of the bedchambers project centered around the main Hemsley Bedchamber used by Colonel William Hemsley and his wife Sally in 1784, and the Guest Bedchamber, which welcomed some of the most prominent visitors of the Eastern Shore of Maryland.

The Hemsley Bedchamber illustrates the practical, multi-functional character of family spaces in the late eighteenth century equipped not only with fine furnishings but also with work surfaces and textiles that balanced durability with refinement.

Among the notable pieces acquired for the room is a late eighteenth-century chest of drawers c. 1780. The top features a molded edge above a sliding writing lid; below are graduated, beaded drawers with brass pulls, set on splayed feet. The piece carries provenance to the local Paca family.

Image 1: Paca Family Chest of Drawers. Cloverfield Preservation Foundation Collection Item No. 2018.8.

Image 2: Buckingham DesK ca. 1760. Cloverfields Preseration Foundation Item No. 2018.1.

Also in the room is a Chippendale-style walnut desk, crafted locally by John Buckingham, who worked locally in Queen Anne’s County from 1760 until his death in April 1764. This dating places the desk firmly within that period. As lady of the house, Sally would have used such a desk for correspondence and household planning, underscoring the dual role of the chamber as both private retreat and working space.

Image 3: Bedstead at Harrision Higgins in APril 2025. Image Courtesy of Natalie larson.

The bedstead was carefully designed to reflect an eighteenth-century aesthetic while complementing the room’s overall furnishing plan. The piece features plain turned mahogany posts with Marlborough feet, an understated yet elegant form consistent with documented regional examples from Maryland and Virginia. The bed was crafted by Harrison Higgins, Inc. of Richmond, Virginia, a second-generation workshop of seven artisans specializing in the reproduction of English and American furniture of the period. The firm has worked for Colonial Williamsburg, Montpelier, Mount Vernon, Stratford Hall, and Winterthur Museum among others.

Image 4: Natalie and Bruce larson during installation, July 14, 2025.

For the cornice, we selected an upholstered cut design with wide swag valances to complement it. The textile, Les Travaux de la Manufacture from Étoffe in France, is a red-on-white toile de Jouy pattern depicting pastoral scenes of countryside workers in a natural setting. Red toile was especially fashionable in the late 18th century and was often chosen for primary bedchambers.

Although the exact pattern used in the space in 1784 is not known, an 1813 inventory of the third Mrs. Hemsley records the use of cherry dimity in this chamber, giving us a point of reference for the household’s red textile choices.

For the floor covering, we installed a reproduction flat-weave, or “list,” carpet from Woodard and Greenstein. Unlike costly imported Wilton and Brussels carpets, which were typically reserved for public parlors or drawing rooms, flat-weaves could be produced locally, were widely accessible, and were often used in bedchambers. Rather than covering the entire floor wall-to-wall, such carpets were commonly arranged as bedside rugs or in U-shaped configurations, as we choose here, providing warmth and definition to the bedstead area.

Image 5: Finished Hemsley Bedstead with Woodward and Greenstein Carpet.

The matelassé coverlet was sourced from the shops at Colonial Williamsburg. This reproduction, known as the William and Mary Matelassé Coverlet, is adapted from an antique example in Colonial Williamsburg’s textile collections. For the installation, modern mattresses and pillows were chosen to provide structural stability. These elements, though contemporary, were carefully integrated with the historically informed textiles and furnishings to approximate the visual effect of an eighteenth-century bed while accommodating present-day interpretive needs.

In contrast to the primary bedchamber reserved for the family, the Guest Bedchamber at Cloverfields was conceived as a stage for display, a carefully orchestrated space designed to impress. Prominent visitors, such as Edward Lloyd IV of Wye House and his family, were frequent overnight guests, as surviving correspondence attests. The chamber also likely accommodated members of Colonel William Hemsley’s extended family, including his sisters, who visited Cloverfields often.

The bedstead was a gift to Cloverfields from estate manager Jim Barton. Its attenuated turned posts, paired with a compound cornice produced by Harrison & Higgins of Richmond, Virginia, represent a restrained but fashionable style commonly seen in Maryland and Virginia during the late 18th century. To ensure a match to the mahogany, samples from Harrison Higgins, Inc. studio were sent and compared on-site to match the period mahogany finish.

The bed hangings are Fanny’s India Floral reproduction fabric, based on a skirt panel dated between 1760 and 1790 in the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s textile collections. The delicate trailing floral pattern in red, blue, and purple outlined in black recalls the popularity of imported Indian cottons, which were prized by colonial consumers for their brilliance of color and lightness of weave.

Image 6: Fanny’s india Floral reproduction fabric, based on a skirt panel dated between 1760 and 1790, in the colonial Williamsburg foundation’s textile collection.

Beside the bedstead, a small bedside carpet from Woodard & Greenstein further enriches the decorative scheme. Its muted tones of pink and tan were selected to complement the floral textile, while also reflecting the practice of furnishing bedchambers with small, portable rugs rather than full wall-to-wall carpets.

Image 7: Finished Guest Bedstead with Carpet.

The installation of the Cloverfields Guest and Hemsley Bedchambers highlights the social functions these spaces held in early national America and the exceptional craftsmanship involved in their recreation.

This interpretive vision was brought to life through the skilled efforts of Natalie Larson, with the assistance of her husband, Bruce, an archaeologist and historic preservationist, for the installation process. Working in seamless coordination from morning to late afternoon, they approached the task like a well-oiled machine, with each detail carefully arranged in advance to ensure a smooth and precise process. From the dramatic cornice crowning the Hemsley bedstead to the delicate trim of the guest bed, the installation unfolded as a work of art in its own right.

By combining reproduction textiles, authentic design elements, and historically informed craftsmanship, this project allows modern audiences to appreciate both the historical significance and the artistry required to bring it back to life.

History Lessons

Local student Lila Clow and her homeschool group visited Cloverfields in mid-October. The field trip was part of their studies about Maryland during the American Revolution. The discussion grew lively when it was learned that Lila is a descendant of the well-known Maryland Loyalist Cheney Clow. Clow’s conflicts with Maryland and Delaware militias, including Col. William Hemsley’s 20th Battalion, were discussed in the last newsletter.

Lila Clow’s homeschool Group, teacher and Chaperones At Cloverfields. From left to right, Lauren Clow, John Clow, Sharon Clow, Lila Clow, Rylee Foy, Genevieve Turner, and teacher Cara Turner, holding Annie Turner.

Flight of the Bumblebee

Until the recent cold snap, the gardens remained abuzz and aflutter with late-season pollinators.

Monarch Butterfiles were a common site in the late-summer garden, but have now left to winter in Mexico.

Both Cloverfields’ deer and staff have enjoyed the delicious heritage-variety apples.

A Visit to Grandmother’s House

In August, members of the Draper family visited Cloverfields to see the restored house and share childhood reminiscences. The Drapers are the children and grandchildren (and spouses) of Elizabeth Carter Draper Brice (1937-2021), the daughter of Martha Greenwalt Callahan (1895-1989) and her second husband, J. Herbert Carter (1905-1997). Elizabeth was born and raised at Cloverfields. The CPF restoration greatly benefited from her memories and the historic photographs she shared from her collection. It was a pleasure to show the family what has been done and hear their stories.

Back row: John Draper, Mary Draper, and Ben Draper, Eddie Draper. Front row: Callie Draper, Taylor Duncan, Elaine Draper Duncon, Ellen Draper, and Brian Draper.

Reaping What You Sow- Changing Agricultural Practices (1705-2025)

Cool air and shorter days have brought an end to the 2025 growing season, and around Cloverfields, cousins Tom Pippin and Tom Carter have fired up their high-tech combine harvesters and brought in this year’s crop of corn and soybeans.

Pippin and Carter are grandsons of Martha Greenwalt Callahan Carter (1895-1989). Her father-in-law, Thomas H. Callahan Sr., bought Cloverfields from Hemsley descendants in 1897. The Cloverfields Preservation Foundation acquired the house in 2017, but the Pippin and Carter families still own and continue to farm the surrounding land.

Cloverfields, built in 1705 by Philemon Hemlsey (1670 -1719), takes its name from his son William’s (1703 -1736) 1726 survey and later patent that combined six contiguous parcels into one 1,622-acre tract called Cloverfields. If visiting today, Philemon and William would recognize the family dwelling, the mile-long drive leading to it, and the arrangement of flanking fields, separated by ditches and hedgerows. The physical layout of the landscape has changed remarkably little since the 1720s, but the men would find other aspects of the Carter and Pippin’s operation alien.

Image 1: Though handwritten, upside down, and challenging to read, look carefully at the 1726 land survey (Left) and you can make out the outline of present-day Foreman Landing Road, Rt. 662 and some present-day field arrangements. Image edited from the original created by Kimmel Studio Architects.

Like most farmers in the area —and, in fact, much of the country —Carter and Pippin grow corn and soybeans. Like Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, these two make a classic pair. Alternating these crops in the same fields improves soil health, increases yields, and diminishes the need for fertilizer and weed treatment.

Corn, by far the country’s most valuable farm product, is native to the Americas. Native Peoples introduced corn to European farmers, who quickly adopted it as their staple food crop. Corn had several advantages over wheat, the mainstay grain of the Old World, including producing more grain per acre, lasting longer, and not requiring threshing before grinding. Profit-minded planters cultivated corn rather than wheat to free up more land and labor for income-producing tobacco.

Image 2: A dried ear of gourdseed corn Source: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Like most farmers in the area —and, in fact, much of the country —Carter and Pippin grow corn and soybeans. Like Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, these two make a classic pair. Alternating these crops in the same fields improves soil health, increases yields, and diminishes the need for fertilizer and weed treatment.

Corn, by far the country’s most valuable farm product, is native to the Americas. Native Peoples introduced corn to European farmers, who quickly adopted it as their staple food crop. Corn had several advantages over wheat, the mainstay grain of the Old World, including producing more grain per acre, lasting longer, and not requiring threshing before grinding. Profit-minded planters cultivated corn rather than wheat to free up more land and labor for income-producing tobacco.

Imag3e 3: A Reenactor at Colonial Williamsburg inspects a tobacco plant for pests. Gourdseed corn grows in the background.

King James’s condemnation that it was “loathsome to the eye, hateful to the nose, harmful to the brain, and dangerous to the lungs” failed to diminish tobacco’s popularity among British and European smokers. It took centuries, but ultimately, King James’s view prevailed. Tobacco has long since vanished from Maryland’s Eastern Shore and is now only grown in limited amounts elsewhere in the state.

Unlike in the rest of Maryland, by the early eighteenth century, wheat began to rival tobacco as the Eastern Shore’s main export. The reasons for this are various and well-documented, but mainly come down to the fact that wheat was easier to grow and usually more profitable. [1]

Although lagging far behind corn and soybeans in terms of acreage planted, wheat, particularly the Soft Red Winter variety, remains a significant crop on Maryland’s upper Eastern Shore.

Philemon Hemsley grew wheat at Cloverfields-- probably a variety known as Yellow Lamas—no later than 1719. [2] By the time of the American Revolution, it had overtaken tobacco as the primary cash crop. As discussed in the previous newsletter, the Eastern Shore produced and shipped so much to Washington’s Continental Army and state militias that it earned the nickname “Breadbasket of the Revolution.”

While modern corn and wheat varieties look different from Gourdseed and Yellow Lamas, the Hemsleys would at least recognize the plants for what they were. Not so with the soybean fields surrounding Cloverfields. This equally ancient staple native to Southeast Asia was introduced to the British colonies first in Georgia in 1765. The green legume with a hairy pod met with a reluctant American market.

Critics declared them “undesirable for table use.” An 1857 editorial in the American Agriculturalist said of them, “We first saw them cooked upon the table of a friend, and were not especially pleased with the flavor. “My wife found them hard to cook and I found them hard to eat.” wrote L.L. Osment of Cleveland, Tennessee.

By the mid-20th century, agriculturalists were hard-selling soybeans, praising them for their superior ability to nourish people, animals, and soil alike. Diners worldwide now enjoy soy products like tofu, edamame, and soy sauce, but most of the nation’s second-most-valuable crop still goes into animal feed. [3]

Image 4: An Eastern Shore Farmer harvesting soybeans at sunset. Source: Delmarva Now.

The most noticeable difference between the pre-industrial agricultural landscape created by the Hemsleys and that of Pippin and Callahan is the absence of human and animal labor. Modern machinery allows a single person to manage hundreds of acres, and trucking to market immediately after harvest obviates the need for most barns, once a defining feature of any farm. In contrast, pre-industrial farming required scores of workers to plow, plant, weed, and harvest; teams of draft animals to pull equipment; and numerous buildings to house them.

Cloverfields' third owner, Col. William Hemsley, died in 1812. His will divided Cloverfields and other real estate among six heirs. In 1825, Hemsley’s grandsons, William H. Forman (1820-1868) and his brother Ezekiel (1821-1875), became the child-owners of 800 acres of Cloverfields, including the house, and also a half-interest in nearby Wye Mill. In 1853, the brothers legally divided their joint inheritance, with William taking possession of the family home and the southern 400 acres. [4]

William H. Foreman’s life spanned a fraught 48 years marked by economic downturns and social upheaval, culminating in the Civil War. Locally, many old gentry families, including close friends and relatives, struggled to stay solvent. During their childhood, financial difficulties led the boys’ guardian, Ezekiel F. Chambers, to consider selling Cloverfields to support them and their mother, then living in nearby Chestertown.

William reached adulthood possessing only a small portion of the land and none of the labor his ancestors had used to build their wealth. Additionally, the once-grand family mansion was in poor condition; the west wall and chimney were on the verge of collapse and required reconstruction.

In 1848, William married the wealthy Marcia Watts of Carlisle, Pennsylvania. The bride was the daughter of Frederick Watts (1801-1899), one of the nation's leading agricultural reformers. While he was a lawyer and judge by profession, his true passion lay in farming and promoting science-based agricultural reform. His legacy includes helping to found the Agricultural College of Pennsylvania, now Penn State University, and serving as Commissioner of Agriculture during the Grant Administration. [5].

The couple's union, not coincidentally, corresponded with a series of much-needed repairs and upgrades to the house.

The Formans' reworking of Cloverfields extended beyond the dwelling to include farm operations. Faster and more reliable transportation systems made perishable commodities such as milk, eggs, and orchard produce practical and profitable additions to cereal crops. They diversified a primarily grain-based operation by significantly increasing the number of dairy cattle and poultry. Decades before the Eastern Shore was known for its poultry industry, Cloverfields had a flock of 264 chickens, as well as dozens of turkeys, ducks, and guinea chicks.

By 1850, the Formans had abandoned tobacco. Wheat and corn production continued, but more efficiently using labor-saving equipment. The 1850 agricultural census valued the farm at $6,000 and farm machinery at $300. The 1860 census puts these amounts at $20,000 and $500, respectively.

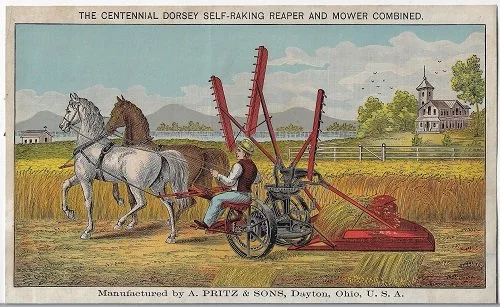

When William died in 1868, among the most valuable items listed in his estate inventory was a wheat thresher ($130) and a Dorsey reaper "with extras" ($100), the latter recently patented by Marylander Owen Dorsey. A Bickford and Huffman seed drill ($15), introduced in 1849, is also listed in his estate inventory [6].

Image 5: The first Dorsey reaper was patented in 1856. The design advertised above was displayed at the 1876 Centennial Exposition held in Philadelphia. The event showcased U.S. Industrial Achievements and signaled the “coming of age” of the young nation. Source: History of the Daytonians, Facebook Group.

Image 6: Smoke-Covered rafters and a charred floor support the claim that meat was smoked in Cloverfields’ Attic.

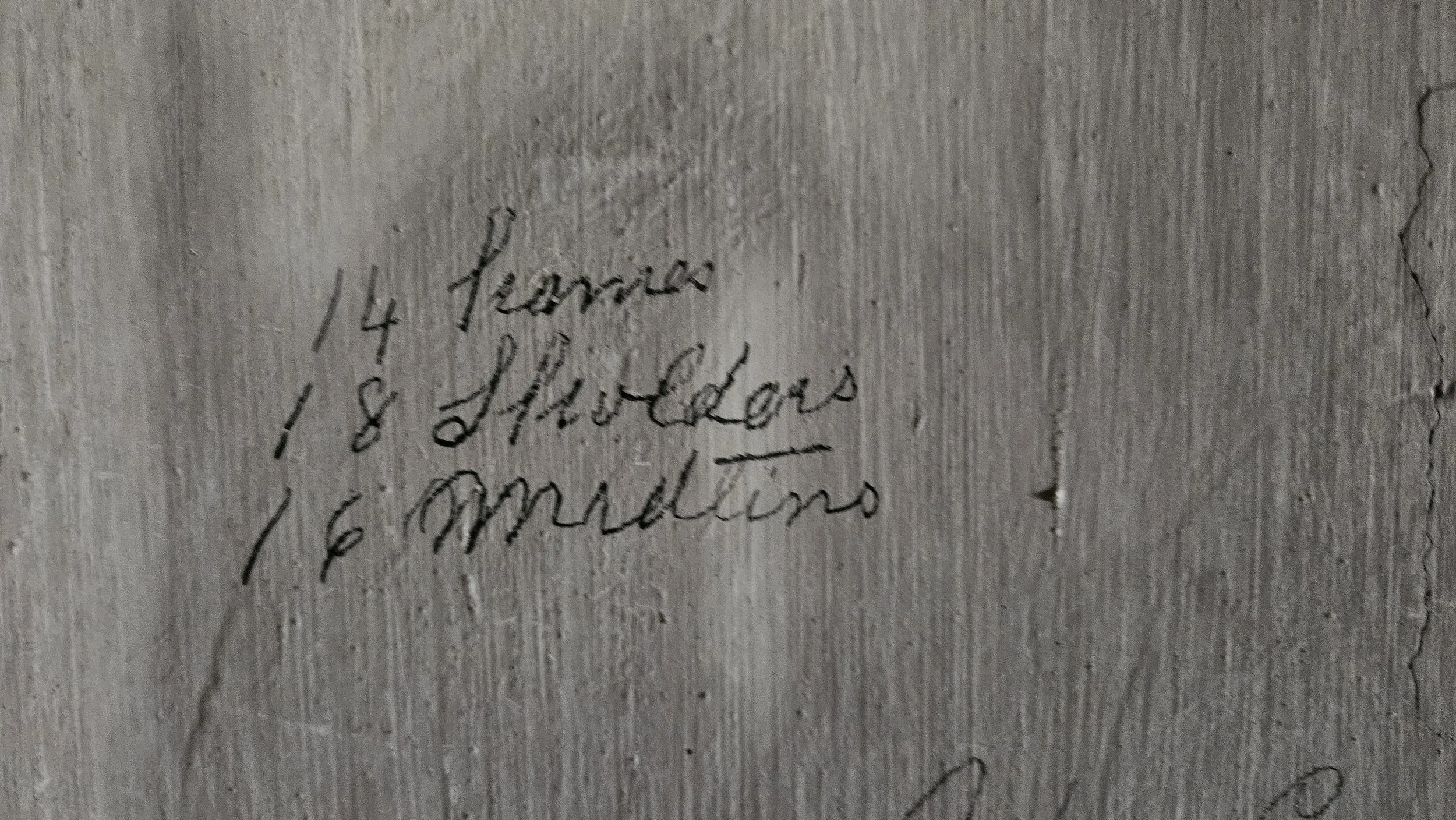

Over approximately 57 years, the Forman family transformed Cloverfields into a modern "progressive" farm. Marcia's estate inventory, taken in 1884, reflects a continued commitment to livestock, as well as the addition of on-site meat processing (ham, shoulder, and mutton).

Oral tradition and physical evidence indicate that meat was smoked in Cloverfields' attic. Curing meat inside the home of a prosperous family that had a new Steinway piano in the parlor below is difficult to reconcile, but probably true. [7]

Image 7: Marcia Forman’s 1884 estate inventory listed 42 hams, 39 shoulders and 44 muttons. The above writting listing the same types of meat is found outside of the so-called smoke room in Cloverfields’ attic.

William and Marcia's marriage produced six children. Three sons moved to Baltimore and became grain merchants, operating under the name Forman Brothers & Co., while the two remaining brothers and the only daughter relocated to different states (Pennsylvania, Georgia, and New Jersey).

In 1897, Thomas H. Callahan, Sr. (1844-1923), an Eastern Shore native living in Baltimore (listed in the federal population census as "capitalist"), purchased Cloverfields from the Forman heirs for $10,000. This raises questions. Why did none of the Forman children stay at Cloverfields? Why did a farm valued at $20,000 in 1880 sell in 1897 for half that amount?

Future newsletters will further explore the Forman years and examine the interesting 120-year Callahan-Carter tenure (1897-2017) that brought Cloverfields into the modern era.

[1] Gregory A. Stiverson, Poverty in a Land of Plenty: Tenancy in Eighteenth-Century Maryland. (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press), 1977, 96.

[2] Estate Inventory of Philemon Hemsley. Probate Records of Queen Anne’s County, Liber 4, Folio 119 (May 30, 1720).

[3] William Shurtleff and Akiko Aoyagi, A History of Soy in the United States: 1766-1900. (2004) https://www.soyinfocenter.com/HSS/usa.php].

[4] Queen Anne’s County Land Records. William H. Forman and Marcia R. Forman, and Ezekiel T. M. Forman and Francis M. Forman. Deed of Division, Liber JP1, Folio 430. ,(May 16, 1853).

[5] Mark W. Podia, The Honorable Frederick Watts: Carlisle’s Agricultural Reformer. (University Park: Penn State Environmental Law Review), Vol. 299, December 2008, 17.

[6] Estate Inventory of William Hemsley Forman. Probate Records of Queen Anne’s County, Liber WAJ 2, Folio 420 (August 3, 1868).

[7] Estate Inventory of Marcia R. Forman. Probate Records of Queen Anne’s County, Liber WET 1, Folio 429 (May 27, 1884).